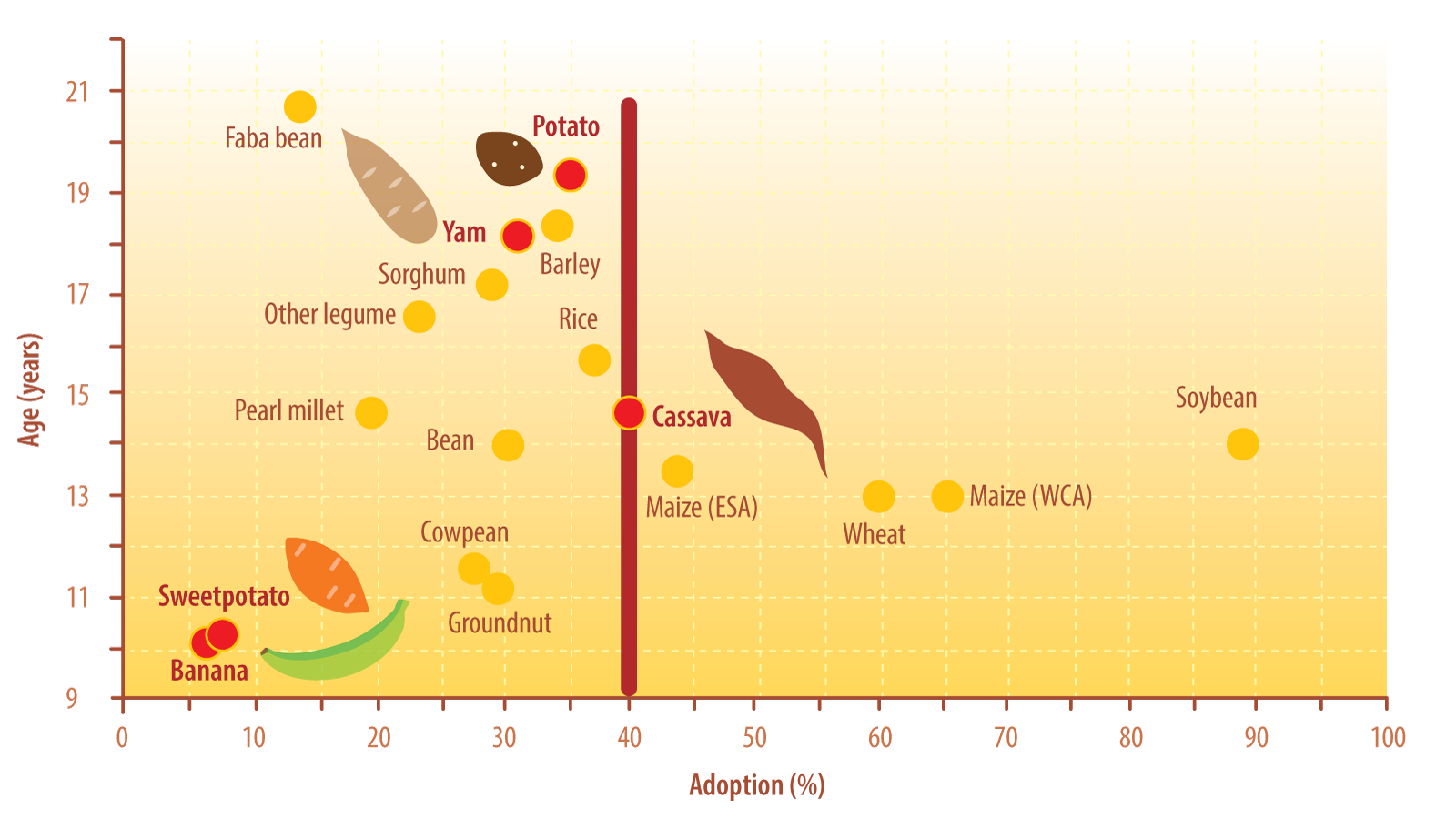

In Africa, the adoption of modern varieties of roots, tubers and bananas rarely surpasses 40% of their potential, a major reason is insufficient attention paid to the crop traits that farmers and other consumers want. Understanding these preferences, and addressing them through breeding programs, can help break through the 40% ceiling and contribute to improved smallholder livelihoods. Fortunately, new breeding tools make this more feasible; breeding programs are seriously committed to capturing real demand and change is underway with the RTBfoods project and in RTB breeding programs.

A team of RTB scientists recently reviewed adoption studies of modern varieties of RTB crops. This revealed that the average adoption rates in sub-Saharan Africa are below 40% of the crops’ area, as though there were an invisible ceiling. One major reason for the invisible ceiling has been the insufficient attention by breeding programs to understanding how consumer preferences shape demand and drive adoption. This is especially important in sub-Saharan Africa where farm households are consumers as well as producers, and because men and women play different roles on the farm and may differ in their preferences. Fortunately, work is underway with RTB breeding teams to incorporate these preferences in new varieties (product profiles) which gives us every reason to hope that we can break through the invisible ceiling (see story in this annual report on RTBfoods).

ADOPTION AND VARIETAL AGE MODERN VARIETIES IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA 2010

More than 44 new banana (and including plantain) varieties were released in East Africa by 2016. But the area planted in these varieties is only about 6% of the total, even though many modern varieties are high-yielding and disease-resistant. Studies showed that adoption was low mainly because new varieties usually failed to meet consumer demands for a specific product type (e.g., for cooking, or as fresh fruit).

In Nigeria, cassava fared better, as modern varieties were adopted on 46% of the crop’s area. Those varieties tended to be high-yielding, which was important as cassava became a commercial crop in the late twentieth century. However, it was also clear that widely adopted varieties were also good for making gari (a food in high demand). Other local varieties meet consumers’ preferences for specific cassava products such as a snowy white color for making abacha, a grated cassava product

In the case of sweetpotato in Uganda, adoption surveys did not examine the importance of quality traits. However, CIP plant breeder Robert Mwanga, who also co-authored the study, explained that “during participatory plant breeding, we found out that many of the attributes that farmers look for were consumer traits, including the attractive color of roots, ‘sweet’ roots when cooked, and mealy and non-fibrous texture. So, targeting these traits is important if farmers are going to adopt our varieties.”

In Côte d’Ivoire, consumers generally prefer guinea yams (Dioscorea rotundata), because they make a good pounded yam. Nevertheless, many farmers have adopted land races of water yam (D. alata), introduced from other regions as a cheaper alternative. Again, a key factor in adoption was a quality preference, and the varieties that were adopted made an acceptable pounded yam, unlike many water yam varieties.

Potato in Kenya has shown particularly rapid varietal change. In recent years, the Shangi variety, likely a farmer selection from CIP breeding lines, has been adopted by most farmers. Sophie Sinelle, of Syngenta Foundation, co-author of the RTB review paper, explains: “in Kenya we found that farmers do like high-yielding potato varieties, but adoption is driven by a combination of consumer and market demand preferences which you can find in Shangi variety, earliness to be the first on the market, and culinary qualities such as taste and quick cooking time.”

As Graham Thiele, lead author and director of RTB, concludes, “a central finding is that despite some recent work there is still a dearth of information to capture and address gender differentiated consumer preferences and procedures to ensure that this information can be addressed effectively by breeding programs.”

A new project, RTBfoods, an integral part of RTB, is working to break through the adoption ceiling. RTBfoods does improved surveys of consumer demand for roots, tubers and bananas. Then RTBfoods translates consumer criteria (like good taste and stretchability of pounded yam) into properties that breeders can recognize, such as starch and fiber content. “While there may not be a gene for tasty or stretchy, RTBfoods is researching the interaction of genes and the environment to help breeders produce these traits in varieties that consumers will value,” says Dominique Dufour, who leads RTBfoods at CIRAD.

SHARE THIS